A day in the life … appreciating the Men’s Room, Manchester

Post by Jenny Hughes

On Wednesday evening last week – a warm, late summer evening in central Manchester – Hulme Community Garden Centre was the site of the final outcome of the latest in a series of artist residencies at the Men’s Room in Manchester. The Men’s Room is an arts and social care organisation that works creatively with young men in crisis, including male sex workers, offenders and homeless young men. The two artists were JSD (otherwise known as Dave Hindley, from the respected Virus Syndicate) and the marvellous Persia (rapper/MC/musician, Olga Niayesh). The Men’s Room methodology blends creative practices – working across multiple art forms – with a unique form of social support characterised by responsiveness, long-term relationships with young men and working closely with partner agencies. At the Men’s Room, in the words of one of the young men I spoke to during the evening, there is always an open door, and you feel like the staff care about you. The organisation offers regular creative and social activity, access to practical advice and support, and a weekly hot meal.

The artist residencies are the brainchild of Men’s Room Head of Creative Development, Chris Charles. The idea here is to broaden the range of art forms and high quality artists in the city with knowledge of and relationships with the Men’s Room, at the same time as providing training to improve artists’ ability to engage groups with complex experiences. Another aim is to introduce a ‘lead artist’ and ‘emerging artist’ model of provision, which creates a ‘stepping stone’ pathway for young men thinking about developing their own artistic practices as creative individuals. I’m working to document this approach for the organisation, and also to carry out a broader piece of research on the history of the Men’s Room’s creative approach as part of the Poor Theatres research project.

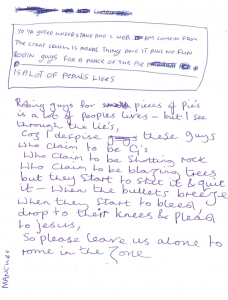

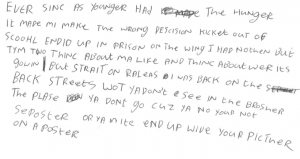

A day in the life … was the motif adopted for the six-month artist residency, which engaged the young men in lyric writing, music performance, recording and production – with the end outcome the event last week, a CD of original tracks and a short film documenting the process. The tracks on the CD loosely tell the story of a young man’s journey into crisis, featuring difficult moments – losing accommodation, family conflict, vulnerability on the streets – that powerfully bring to life the challenges of the young men’s lives. The emotional intensity of the work produced was what surprised me most – there’s something about the quality of this art form (the young men were working with spoken word, rap and hip hop) and the dynamic, open-hearted and sensitive approach of the two artists, that encouraged the young men to scribble some searing phrases onto paper, working with each other and the artists to develop these into brilliant soundtracks.

The Men’s Room works within a specific framework of social care and with economically disadvantaged young men. As an aside – as we proceed with the Poor Theatres research – a range of intentions for arts, theatre and creative initiatives with economically hard up communities is becoming identifiable. There are at least five areas in the range, and they overlap, in that examples of practice in real life traverse more than one category. They are – 1) activism – arts initiatives explicitly linked to economic justice aims, for example resisting gentrification and/or otherwise drawing attention to economic inequality; 2) social care – arts initiatives as part of a network of social support for vulnerable and/or disadvantaged individuals and groups; 3) community building and expression – creative social practices building identities, resilience, sustainability and well-being of communities; 4) education – art as a means of engaging disadvantaged young people in education; 5) arts for economic development – especially discernible in the evident growth of creative entrepreneurship initiatives, working with a particular notion of a creative economy.

To return to the Men’s Room – one of the many things that is interesting about this organisation is the way it works critically with the imperatives of ‘self help’ and ‘self care’ demanded by neoliberal forms of education, welfare, work and community practice (I talk about the latter in a previous post ‘The neoliberal politics of social theatre’). Since writing that post, I’ve read Michel Feher’s article ‘Self appreciation; or, The Aspirations of Human Capital’ (in Public Culture, 21:1, 2009). To condense a complex argument somewhat – Feher notes how the neoliberal economic context in which individuals (and, we might add, small and precarious organisations like the Men’s Room) survive, creates specific forms of ‘subjectivity’ and ‘subjective relation’. Previous to this context, under a liberal economy, a person sells her/his labour to an employer, who profits from that labour – with autonomous forms of subjectivity produced because the economic relation allows workers’ to negotiate a better deal. The ‘liberal subject’ appears as an autonomous agent, and there is a resultant secure separation of some experiences – love, sociality, creativity, welfare – from the economic calculus. Under a neoliberal economy (where post-industrial conditions of production have altered class identifications and changed experiences of work) the free worker negotiating terms of labour has been replaced by ‘human capital’. This has, in turn, produced a different kind of subjectivity – ‘my human capital is me, as a set of skills and capabilities that is modified by all that affects me and all that I can effect’ (p. 26). Instead of dealing in a labour market, we focus on ‘self appreciation’ – rather than maximising the return on investments of time and work, we have to ‘constantly value or appreciate ourselves’ (p. 27) in conditions that are difficult to predict. Feher makes useful reference to Barbara Cruikshank’s brilliant book Will to Empower (1999) here – which focuses on how discourses of self esteem, self confidence and empowerment have become part of practices of government and informal as well as official welfare systems. Interestingly though, Feher argues that we embrace ‘self appreciation’ as a means of critically engaging with a neoliberal economic context (just as workers negotiating better working conditions embraced their status as free workers, with all of its concomitant conditions of exploitation). Embracing ‘self appreciation’ as a critical and creative response to the contemporary moment means that we can contest ‘what constitutes the basic conditions, the criteria, and the required means for self-appreciation’ (p. 39), from a position of recognising the legitimacy of people’s desires ‘to increase the value of their existence’ (p. 40). Here – rather than working from recognition of interests held in common – people work together ‘in the name of their common desire to make their lives valuable’ (p. 41), raising from their own perspective ‘the question of what constitutes an appreciable life’ (p. 41).

The Men’s Room can be looked on as an example of this in action. As told through fragments of stories and experiences vocalised via A day in the life …, Men’s Room participants create artwork from a starting point of extremely fragile self esteem, a profound lack of self value, that they see mirrored back to them externally as well as can experience internally. At its best the project manages to open up a series of creative experiences whereby some participants can express themselves, create a piece of art, be applauded. Providing a set of experiences that help improve self-image and self confidence is an explicit aim. At the same time, the offer of social support is open-ended and sustained. If you miss an appointment, another is offered, and there is no policy of ‘so many strikes and you’re out’ – or anything like that. With the regular personal crises that are almost permanently rumbling through the participant group, and a social security system that, as a result of economic policies of austerity, is at its bare bones – this becomes increasingly demanding, and even more important for staff to sustain.

A peculiar kind of ‘appreciation’ is the bedrock of this – the young man I chatted to on Wednesday emotionally described the impact on him of staff being visibly moved when a young man who attended the project last year committed suicide, and at another time, when they noticed that he himself was not ok, without him having to say anything. Here, there is a powerful sense that – if you are not ok, I am not ok. ‘Appreciation’ doesn’t accumulate in values to be cashed in, but is experienced in the moment and sustained by a regular and reliable infrastructure of attentiveness and support. It isn’t conditional on the young men ‘moving on’, or ‘getting better’ – although this is often desired – rather, appreciation accrues and is held in place by a regular appearance of creative practice and social support. The ways in which ‘self appreciation’ is not cashed in or paid out is important – the value accruing here is not appropriated, owned and exchanged, but is carefully attended to in the short and long-term – the practice of value is im-proprietorial rather than proprietorial. The opposite of a rationing mentality is in play – here, inputs (great artists, responsive social support, sustained relationships) do not lead to outputs (‘functional’ young people), based on identified deficits (‘problem’ young people). Rather, there is a more entrepreneurial, open-ended, creative, spontaneous and risky spirit in play, one which sees potential abundance in every sparse nook – where each person in the room has value (as an artist at some stage of development), and practices of relation and investment might accrue extraordinary ‘dividends’ in ways that are impossible to predict at the outset.

For more information on the Men’s Room –

Watch this space! Over the coming month or two, a series of filmed interviews with Men’s Room staff past and present, excerpts from lyrics and tracks from A day in the life …, and a scrapbook of examples from other creative projects will be uploaded to the Poor Theatres map and database. Follow @PoorTheatres and https://www.facebook.com/PoorTheatres for regular updates.

For the early history of the Men’s Room – read Janet Batsleer’s article – ‘Voices from an edge’ Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 19: 3 (2011)

For my own attempt to capture the Men’s Room approach – ‘Queer choreographies of care’ RIDE: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 18: 2 (2013)

For a research report exploring how Men’s Room participants survive in the city, researched and written by myself with Alistair Roy, and commissioned by the Lankelly Chase Foundation – Surviving in Manchester (2014)

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.