Carran’s Working Diary 28: Writing on the Wall 4: SkEtching a Visitor

I haven’t been here for a while but I am here now. This particular visit is important to me because it means I am not alone. Thank you.

I haven’t been here for some time because I got a new position in a big place in Beetham, Cumbria. It is a mill. I have been working there in a fully occupied sort of way since I last wrote about my time in the Working House, this Working House; this space where you come and visit me and read these random thoughts.

I don’t want to lose favour with you, my generous visitors, so I am writing again to inform you of my progression through the steps to my current position and to make you aware of how much you have helped me along the way, for which I am forever grateful.

Thank you very much,

Thank you very very much,

Thank you very very very much.

Whilst in the Working House, for that long time last year, I read about how visitors to workhouses and particularly female visitors as aspiring guardians eventually did become guardians, once they too had “worked their way up” so to speak, doing good works, writing about it, getting the vote and so on. The position afforded women had been sometimes limited because of their inequality with men and the fact that there wasn’t a vote for a woman in those days. So those of you, dear visitors, whom I have read about had little power or influence but I realise had felt compelled to enquire enough even to go undercover and experience for yourselves what it is like to be in need. In fact some of you are currently doing this on the television[1] but I guess those of you involved are not doing it for nothing as some of you so generously did back in the old days before television.

People don’t tend to do something for nothing nowadays do they? I include myself in this sorry state of affairs. Even though I have achieved a better position now, working at the mill, I still want paying for my efforts, because I don’t think will have much of an old-age hand out, when the time comes, and it will come. Incidentally, is it really a handout when I have paid for the actual stamp? What is the difference between a pension and a hand-out?

Anyway, going back to the people who did do something for nothing in the old days, you know, if it wasn’t for the likes of people like Margaret Wynne Nevinson[2] and Mary Higgs[3] (and many others no doubt who do not get a mention in dispatches) nothing would have been done to change things in terms of promoting women to higher positions of responsibility within a new caring system, I mean the new Welfare System or State that has been coming about. Where would we be without women like Margaret and Mary? These people dug deep into their hearts and their pockets to discover what it was like to actually do something for nothing… I mean, to just do it for food and water and the occasional beer, not for any luxury or whatever. Of course it was probably always nice to return home to the big house to reflect on the dangerous adventure whilst getting warm and comfy over a muffin and hot chocolate.

But, dear visitor, I am interested in the contradictions presented to these women; privileged do-gooders and aspiring practitioners, they seem to be. What motivated them? I imagine it was quite fulfilling and made a person feel good about themselves if they could help: like when you dig into your pocket, find a £2 coin and happily toss it into the hands of some unfortunate one sitting with a dog on a street corner.

Their motivation might also be similar to our Matron’s who aspires to be a guardian because her position is under threat and because, I think, deep-down, she thinks she can change the system from without rather than from within. She could be cut out of the system altogether; tossed on the scrap heap like a 1p coin dropped in the gutter because it doesn’t really count for much, just the bit left over from something costing £1.99. I am so amazed at the many pennies I see just tossed away these days. I could have bought a teapot and several muffins with them by now.

As you may know, Matron is being moved on because she is not really required to run the house on her own anymore. She has been presented with alternatives to her husband but she finds it a bit difficult to work with the newly appointed male counterparts who never stay long. You know, her husband passed away and was very ill for some time before that so she has been running the house on her own with some degree of success. Her concerts are pretty amazing. Anyway, because of the rumpus and staff coming and going, the Guardians have decided to find a replacement for her – a statutory couple, they will wait till she leaves voluntarily and they will make sure she volunteers to leave. She doesn’t have much choice in this change in her contract of engagement for she has not yet got the vote and she doesn’t have a union or anything like that. Even if she did have the vote it might take some considerable time to change the law about these things.

Don’t go away

In order to be fair to anyone visiting this post who may by now be completely flummoxed, baffled and confused… let me skEtch this visitor notion for you in a little more detail by coming clean and losing this capricious persona for a moment.

Sources, Committees and Guardians

It is somewhere between 1834 and 1916 (the year of the New Poor Law and the year my nana-in-hospital first went into a hospital aged 17, one of two former workhouses I now realise she inhabited) Did she have any visitors?

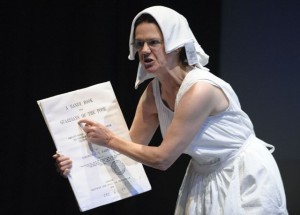

The Matron and the Funraiser characters in “The House” performance came from reading Higgs and Nevinson[4] and also to some extent from an event on Homelessness I attended at the Royal Exchange, Manchester[5].

Also, my mum has talked a lot about “the committee” who visited and “checked up” on the children’s home she lived in during the early 1940s. She talked a lot about performing shows for this committee and also for American soldiers who visited the home while stationed nearby during the Second World War. “We were always doing bloody shows,” she said recollecting the over-enthusiastic Assistant Matron who made her sing “Three Little Shoemakers Are We” with boot nails in her mouth. I guess the Assistant Matron was looking to combine the quality of the musical sketch with a sense of realism and her theatrical endeavours presented her with an economically viable unpaid cast. Performing to impress was paramount because making a good impression might mean donations and it certainly meant a good note for the producer and donors in the minute book!

“The children and staff spent a very happy Christmas. Owing to the kindness of the Committee and friends every child found a well filled stocking on Christmas morning, and also received a gift from an illuminated Christmas tree. Some of the younger girls gave an excellent concert, which reflected great credit to Miss Thompson who trained them.” [6]

Also see this reference to Guardians in an extract from George Sims’ ballad[7]:

It is Christmas Day in the workhouse

And the cold, bare walls are bright

With garlands of green and holly,

And the place is a pleasant sight;

For with clean-washed hands and faces,

In a long and hungry line

The paupers sit at the table,

For this is the hour they dine.

And the guardians and their ladies,

Although the wind is east,

Have come in their furs and wrappers,

To watch their charges feast;

To smile and be condescending,

Put pudding on pauper plates.

To be hosts at the workhouse banquet

They’ve paid for — with the rates.

This ballad was an early textual stimulus for “The House” presenting an interesting example of the permutations of audience/visitor and performer/pauper relationship.

Councillor Robert Clegg[8], who contributed generously to the research for “The House” with regard to Birch Hill Hospital/Dearnley Workhouse in Rochdale, referred to the committee in these places as comprising “the great and the good”, and how some served for years and years without any form of selection process. He also referred to the subsequent system of accountability, which drove in the changes that formed the new Hospital Trusts when he served as CEO for the Rochdale Healthcare NHS Trust. The historical basis for these checking systems gave me food for thought.

In 1942 or thereabouts when my mum was in care, the Victorian role and notion of Guardians had been replaced by the Local Authority but the Committees comprising of “the great and the good” were still in place. I think there has always been a fluidity between the guardian role and the committee role since the New Poor Law. Guardians were usually people from occupations like magistrates, business men, doctors, lawyers, vicars: men with high flying jobs. They would check up that the staff (the Master, his matron and their ancillary staff) were doing their jobs properly, i.e. spending the ratepayers’ money wisely and accounting for every penny. The intentions were honourable but like today how might the accountants be accounted for?

This committee work is voluntary, so no wages for it, but expenses are paid, rather like voluntary work in some arts projects I have known. However in the case of the guardians, the committee, the local parish, the ratepayers, they all pay indirectly through their rates. These people want to see that they are getting a good deal here because in a sense they could be paying to volunteer as well as volunteering. They want to see that their money is spent well and not squandered on undeserving scroungers.

In “The House” I am playing with these “contracts of engagement”. I ran a long way with the idea of people coming to check the “performance indicators”. I played with the idea of the free show and the donated food and how much people might be willing to donate by digging deep into their pockets when in actual fact they have given a lot already. When does voluntary giving verge on extortion? The performance itself was subsidised through whatever means the AHRC[9] raises its funding. The idea of the carousel of money being exchanged and the ultimate difficulty of working out if anything is really free or a hand-out in the end made my head spin sometimes, for lack of a degree in economics. However, the dance and spin of this I hoped made a rich compression of roles for the audience/visitors to “The House”, challenging notions and negative connotations of donation, scrounger, hand-out, benefit, relief, welfare and so on. By placing myself as “up for” being checked up on, all my characters were to some extent being checked up on and assessed by a non-paying audience.

The Outside Eye

Whilst making the work, before I had a real audience, my visitors were those who looked at my work. A director is a first audience to some extent. I didn’t have a director. In these early stages only three people saw what I was doing and commented on it.

Jenny Hughes, who leads the entire Poor Theatres project and commissioned “The House” came along on several occasions: to an initial showing of material; the scratch performance, rehearsals the week before the showing where she was involved in some editing of the script and to sessions concerning the research throughout the project where she would record our conversations about the research performance as it developed. Two of these conversations can seen here

and here

Maggie Gale who has known my performance work since the early 1990s came along to the pre-scratch showing and then offered some outside eye contributions on a couple of sessions before the scratch performance and then offered several sessions before the final showing.

Richard Talbot, a collaborator in previous performance work saw the pre-scratch, the scratch and the final showing and he also showcased the work at Salford University.

I had intermittent/interruptive visitors who didn’t realise they were visitors: workmen, security men, technicians, cleaners and a photographer, even whoever checks up on the security cameras.

The Audience

Then of course there was the mass of visitors who became the audience for the work during the scratch and final showings in 2015.

I have played with many permutations of the audience/visitor in order to frame a relationship my relationship to them and it was deliberate that these visitor roles should shift and change throughout the playing of the piece. The full understanding of this still rests within the “visitor’s book” that is emerging from the feedback we have had on the performances so far. These reports – short and long, in the form of questionnaires, essays, creative responses, accounts and reviews – this “checking up” could be a lifeline, a continuation of the work. They might fill a stocking and keep me in work for some considerable time or at least in voluntary occupational therapy for the foreseeable future.

A Haunting

But before I wrap up I do want to mention some other kind of visitor that belongs in a phenomenological sphere. I had a few visitations whilst making the work:

Enter Lady of the Clock Tower whom George Genesis, the Porter at Birch Hill evoked. Enter Beattie, Phylis and Alice, residents of Birch Hill who were the Rochdale contemporaries of my Suffolk nana-in-hospital and whose stories were evocatively described by Robert Clegg and Chris Selim featured on “The House” soundtrack.

Re-enter nana-in-hospital herself who materialised again through postcards, scrapbooks, revisited diaries, night and daydreams, secret hospital files and adoption papers. In comes Grandad Daynes made manifest through his politely written notes to the authorities concerning his delayed paternity payments and famous for a moment in the London Gazette when his brothers’ drapery business failed in 1934. Then up comes a whole host of ancestral phantoms drummed up through hours stolen in Southport Library searching ancestry.co.uk.[10], secret hours revealing a web of poverty stricken Harveys and Rudlands whose ghosts drove horse-drawn ploughs, went to war, washed clothes, lived in asylums and kept their own houses clean and lived cheek by jowl while over time their lives were silenced by regulatory systems that checked up on them, ultimately shredding the evidence after the seventh year.

Re-enter nana-in-hospital herself who materialised again through postcards, scrapbooks, revisited diaries, night and daydreams, secret hospital files and adoption papers. In comes Grandad Daynes made manifest through his politely written notes to the authorities concerning his delayed paternity payments and famous for a moment in the London Gazette when his brothers’ drapery business failed in 1934. Then up comes a whole host of ancestral phantoms drummed up through hours stolen in Southport Library searching ancestry.co.uk.[10], secret hours revealing a web of poverty stricken Harveys and Rudlands whose ghosts drove horse-drawn ploughs, went to war, washed clothes, lived in asylums and kept their own houses clean and lived cheek by jowl while over time their lives were silenced by regulatory systems that checked up on them, ultimately shredding the evidence after the seventh year.

Well almost, because there is a remnant left by great grandghost; a remnant I didn’t know about before I began working on “The House”. The remnant is in an asylum ledger and the ledger is manifested in a single photocopy read by one who stands, a shadowed figure in the wings, whispering her request for a brief epilogue centre stage. She reads her life to me from the now closed document revealed just as the curtain came down on the piece. It is because of this visitor the piece is not yet finished.

Thank you very much

Thank you very very much

Thank you very very very much

Notes:

[1] http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05wcwg0 accessed 15 March 2016 and http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00lfhhx accessed 15 March 2016

[2] Workhouse Characters, and Other Sketches of the Life of the Poor (1918)

[3] Glimpses into the Abyss (1906)

[4] Ibid

[5] 11th April 2014

[6] Minute Book circa 1943

[7] George Robert Sims The Referee (1877)

[8] featured on “The House” soundtrack

[9] Arts and Humanities Research Council

[10] The Genealogy site

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.