Gaffs, dukeys, geggies and penny theatres

I invited Ann Featherstone, Victorian theatre researcher and novelist, to write a guest post on penny gaffs (partly in response to the ‘Beggar’s theatre’ post – see September 2014 archive). Here it is!

Penny gaffs, penny theatres, penny dukeys, geggies were all slang words for unlicensed entertainment spaces in the first half of 19th century, although the term lingered on into the 1950s. Like all slang words, it often meant what the user wanted it to mean. It usually disparaged the quality of a theatre or hall or the quality of acting; it presupposed that everyone knew what it meant. The Era, that upholder of theatrical tradition, never used the word gaff, but always referred to a ‘penny theatre’ or an ‘unlicensed theatre’. Whatever, the penny theatre was understood. It was a performance space, often ‘found’, and it provided cheap, very cheap, entertainment.

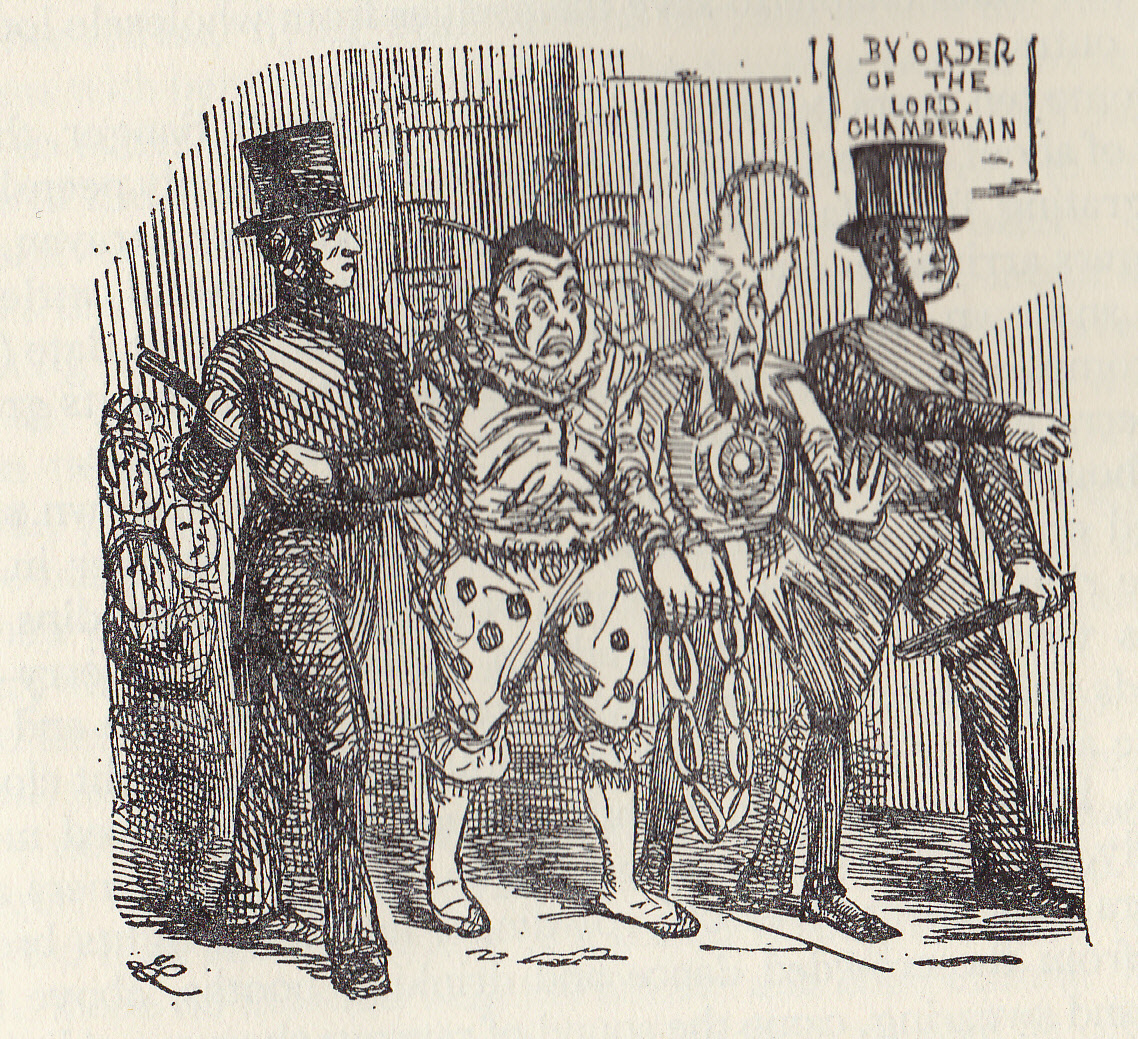

And it was not licensed. Gaffs proliferated during the 1830s in response to the high prices charged by the patent and minor theatres in major cities. Unlicensed, unpoliced and, thus, outside the law, they were a working class response to the restrictions which made the spoken word the prerogative of those who could afford it. Repression, suppression and confusion followed as legislators, magistrates and police attempted to negotiate the complexities of an unworkable law. The Stage Licensing Act (1737) was the rule of thumb. Under this law, the entire company (16 people) of a penny theatre in Short’s Gardens, St Giles, was arrested as rogues and vagabonds. During this period, most complaints about penny theatres which reached the courts were as a result of summonses for nuisance – noise, rowdy behaviour – or being the scene of brawling, thieving and runaway children. But concerns about the ‘immoral tendency and depraving effects’ of the theatres continued and when, in 1839, the Metropolitan Police Act was introduced to extend the powers of London’s police force to cover a multitude of potential ‘nuisances’, the penny shows were ripe targets. The police were given the power, to ‘enter into any House or Room kept or used within the said District for Stageplays or Dramatic Entertainments into which Admission is obtained by Payment of Money, and which is not a licensed Theatre,’ and once there, they could take everyone into custody, performers and spectators alike. Hayden’s penny theatre in Holborn was the first to be made an example of with, perhaps deliberately, the spectacle of the company parade through the streets to court in the stage costumes in which they had been arrested.

Various Acts of Parliament followed in an attempt to make sense of it. The Police Act saw a rise in the number of police raids but little diminution in the number of penny gaffs. The Theatres Act of 1843 clarified the legal position in some ways but complicated it again in others. Under this act, the theatre building had to be licensed in order for stage plays of any kind to be performed, but then another knotty question arose – what constituted a stage play?

Penny theatres came in many sizes; one in Marylebone, London held but 100 people, whilst a former foundry in Ancoats, Manchester held over 600. Facilities also varied. Some really were of the ‘rag and stick’ persuasion, whilst others had as good facilities, and often better, than the licensed theatre around the corner. They might be lean-to’s with a canvas roof at the back of a shop, a liminal space, neither inside nor outside. One of the most intriguing was a converted dwelling house on Whitechapel Road where the house was almost gutted except for the upper floor which was converted into a gallery, accessed by stairs set at 50 degrees, ‘no balusters’. (This almost unimaginable construction was the inspiration for Tipney’s Gaff in my novel The Newgate Jig.)

John Mathews claimed that Hamilton’s dukey in the New Cut, Lambeth, was ‘in company, scenery, machinery, and dresses … far in advance of many minor theatres even of the present day.’ And Mathews would know, for his experience of the dukeys was extensive. He played Mazeppa and Richard Gloucester in Billy Tooke’s New Cut establishment, and at Hector Simpson’s gaff appeared in Valentine and Orson:

“Orson, Mr John Matthews; real armour, set scenes, three sets of platforms for processions, silk banners, and a real live Bear, who during the forest scene stole three candles that formed the foot lights and devoured them, all for a penny!”

Simpson had been a successful performer, perhaps closer to the sawdust than the boards, but appearing at Astley’s Amphitheatre and Sadler’s Wells with his sagacious dogs, Lion and Carlo, and his ‘Wonderful Real Bear’. The gaffs were the last resort of performers on the way down and youngsters, like Mathews, looking for experience and a foot on the ladder. Mathews’ fellow performers at Simpson’s gaff all went on to have careers in the theatre, hardened, no doubt, by their early experience, for Simpson’s was a ‘gagging’ theatre – no script, ‘make up the argument yourself.’ This, said Mathews, was ‘acting with a vengeance.’ Although he was reluctant to say that he was impressed by what he saw at the Warren penny theatre, Austin Fryer certainly found it interesting:

Till I heard visited it, I had never suspected the existence of a society for theatrical entertainment where all imitation is cast to the winds, and originality is fearlessly pursued; their own dramatists reflecting the manners and customs of their own class on their own stage, to their own kith and kin, their ambition, only to please – their thoughts never bent on other reward.

Maybe the question we should ask about the gaffs is not what was performed there, but how.

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.