‘Sinking stages’ – Jeremy Bentham and the education of pauper children

Post by Jenny Hughes

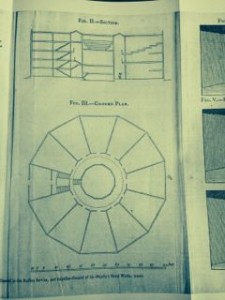

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), famously Liberal and utilitarian, is perhaps best known for his advocacy of ‘panopticon’ architectures for prisons, asylums, hospitals and schools. A panopticon is a circular building, with cells on an outside perimeter and an inspection tower in the centre. They are constructed according to a ‘central inspection principle’ which means that each person is observable, and will feel herself or himself to be observed, at all times, without knowing whether she or he is or not. In the 1970s, Foucault used the panopticon as a motif for describing modes of social control in contemporary society, where social subjects have – via technologies of surveillance instituted in schools, prisons, institutions of care and reform – become effectively disciplined without need for the overt modes of control of the middle ages (dungeons, hanging, the guillotine etc). (in Discipline and punish – bibliography below)

Bentham thought that the panopticon would be ideal for workhouses for paupers, as described in his extensive writing on the poor laws in the 1790s. Here are three photos of the new ‘Industry Houses’ based on the panopticon design in Bentham’s papers (taken from Volume 2 of his Writings on the Poor Laws – see bibliography below). These proposals are important for understanding the poor law – Edwin Chadwick, chief architect of the 1834 poor law, was Bentham’s secretary for many years, and the influence of Bentham’s ideas can be very clearly seen in the poor law principles and policies.

Perhaps less well known than the panopticon idea are Bentham’s proposals for the education of pauper children to be carried out in these new pauper panopticons. I found these ideas quite startling – and not at all what I expected. I had a view of Bentham based on Dickens’ famous critique of utilitarianism in education in his novel Hard Times, where the children have numbers rather than names, are taught ‘Facts … nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life’, and ‘girl number twenty’ is harshly berated for suggesting that a carpet with flowers would be a pleasant thing to have in a home (a carpet with flowers = ‘fancy’ rather than ‘Fact’). The news is – Bentham’s ideas about education are both (a) more humane than this – he advocates strongly for play, music, other activities for the purpose of stimulating the greatest happiness amongst children AND, at the same time, (b) far worse than Dickens depicts. So for example, Bentham argues for a pauper management system based on the East India Company – that vanguard of free market capitalism – and here the poor are to be put to work in ‘industry houses’ that are made profitable, primarily, via CHILD LABOUR!

In the industry houses, all paupers work to cover the expense of their care, with the ‘extra-ability’ – the energy, strength and talent – of poor children increasing productivity, meaning that the entire endeavor will reap a profit. In the time left over from labour, children will be educated, so as to be able to continue to contribute to the community when they are released (which, according to Bentham’s calculations, would not be until they had reached around 20 years old, given the need to make the industry houses profitable via their productivity).

When considering the system of education to be developed in the pauper panopticons, Bentham spends some time describing suitable play and athletic activities. Whilst the ‘seminaries of the opulent’ provide ‘superior opportunities’ for play was well as work, the industry house schools would not afford so much time for play ‘nor ought they afford any sort of play but that best sort, which is work at the same time’. Bentham goes on to say that there should be opportunities for running, leaping, dancing, capering – but they must be linked to industry. This might happen via a structure called the ‘sinking stage’, which can be put to use for the purposes of pleasure, productivity and profitability, all in the same moment. The ‘sinking stage’ is described twice in Bentham’s published writing on the poor laws – I think this is the best description:

‘Sinking stage, for producing an up-and-down motion by the weight of children. A stage hanging at one end of a beam, with the other end of which is connected the burthen: water (suppose), to be raised by a bucket or by a pump, whether of the lifting or forcing kind. A certain weight pressing upon the stage causes it to sink. Children, each of a known weight, would in a certain number produce the effect. The length of the stage is adapted to the proposed number of the children, and runs in a direction transverse to that of the beam: to arrive at the stage they run up an inclined plane. The stage may have two stories: the upper, requiring a longer hill to climb, will be for the older and stronger set of children. It might also, at each story, have two returns, parallel to each other, and at right angles to the first stage: the three together forming three sides of a square. The sport would be, to which could first get into his place. Contrivance will of course be requisite to prevent the children from receiving hurt by any considerable disproportion produced on the sudden between the power and the burthen; but this is no more than what any mechanist will know how to provide for …’ (Jeremy Bentham edited by Michael Quinn, Writings on the poor laws, Volume 2, 2010, p556).

(are you struggling to conceptualise this? – I have been! The other description is on p173 of Volume 1 of Bentham’s Writings on the poor laws – see bibliography below – if you want to see if that helps)

So – the aim is to provide an opportunity for play, pleasure and exercise, but also to but the energy expended by children in play to pecuniary uses. The power produced by the machinery here would presumably be directed in some way to speed up production. This is needed because, for Bentham, when pauper children are being educated: ‘no portion of time ought to be directed exclusively to the single purpose of comfort; but amusement, as well as every other modification of comfort, ought to be infused, in the largest possible dose the economy admits of, into every particle of the mass of occupations by which time is filled’ (p555-56).

A bit like Charlie Chaplin, playing whilst getting crushed in the factory machine, in his film Modern Times (1936):

(note for colleagues from UK Universities – one of my workmates at Manchester mentioned that the recent REF exercise – a national exercise for assessing research in the UK – made him feel like this!)

Bentham liked to express his ideas in architectural form – as with the panopticon, so with the sinking stage. Perhaps we can follow Foucault’s lead here, and try to conceptualise the sinking stage as a form that has been reproduced inside educational practice through history, without it actually having been built (there were no panopticons built in England, despite Bentham’s vigorous campaigning over many years). Like the panopticon, we don’t need to see the material architecture of the sinking stage to sense its presence.

Might a sinking stage be present, for example, in the embrace of creative education in schools in the late 20th and early 21st century in the UK, whereby the teaching of creative subjects such as art, drama and music, were reinvented inside a new utilitarian paradigm and tied to outcomes such as ‘improving employability’ of young people. Ken Robinson’s work in this area has, on the one hand, been extremely important in providing a framework for maintaining the status of the arts in education globally, but on the other hand, perhaps uncritically embraces this new utilitarianism (you find his approach brilliantly summarised via the RSA animated TED talk available here – http://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_changing_education_paradigms).

‘Creativity’ is now a personal capacity, linked to survival inside the increasingly uncertain and precarious labour market of the 21st century. Helen Nicholson has spoken about pressures on children and teachers to ‘be more creative’ in illuminating terms (see chapter 5 of her book, Theatre, education and performance). Joe Winston provides a heartfelt and powerful plea for a return to providing opportunities for children to encounter beauty in education, arguing that ‘beauty is what we fall in love with’, and, as such, does not need to be justified in terms of its worth, but has its own point (in his book Beauty and education).

For me – I like that Bentham called these ‘sinking’ stages – I certainly have a sinking feeling when I sense the absence of my own preference for (and childhood experience of) free, unsupervised, undisciplined, completely purposeless, often dangerous, very dirty and extremely pleasurable play from past and present scripts of children’s education and development – but that’s another story.

I also have a ‘sinking’ feeling when observing the increasingly precarious place of drama in schools in England under the current coalition government in the UK, with its preference for exam based subjects and its marginalisation of the arts, justified as a part of a supposed drive to improve standards.

Bibliography

Jeremy Bentham (2008 [1791]) Panopticon; or, the inspection-house, Dodo press

Jeremy Bentham, edited by Michael Quinn (2010) Writings on the poor law, volume two, Clarendon Press

Jeremy Bentham, edited by Michael Quinn (2001) Writings on the poor law, volume one, Clarendon Press

Michel Foucault (1977) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison, Penguin

Helen Nicholson (2011) Theatre, education and performance: the map and the story, Palgrave Macmillan

Joe Winston (2010) Beauty and education, Routledge

The Transcribing Bentham project is a brilliant source of information on Bentham – http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/transcribe-bentham/

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.