Temperance drama and the poor

Post by Jenny Hughes

I’ve been looking at temperance entertainments in a Rochdale workhouse in the 1880s – as part of a broader project to explore what can be learnt about the early histories of ‘social theatre’ or ‘applied theatre’ from theatrical engagements with the poor in 19th century workhouses (see previous posts). Temperance entertainments during the nineteenth century were many and various, and appeared across the contexts of commercial theatre, amateur theatre, rational recreation initiatives, Sunday schools and chapel life as well as in specially built temperance halls. Not the subject of this post, but it is worth mentioning in passing that the Band of Hope was an extraordinary movement that was part of this – the first organisation devoted to social and recreational activity for children and young people, it rolled out across Britain and its colonies through the nineteenth century (and still exists today as Hope UK – providing drug and alcohol education for young people – see www.hopeuk.org).

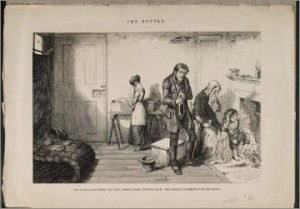

Temperance activity was inherently performative as well as reliant on public performances to disseminate its message. So for example, temperance entertainments tended to culminate in a collective taking of the pledge of abstinence, spoken out loud or signed in the presence of witnesses, and the wearing of a ribbon to publicise one’s commitment to abstinence. Temperance dramas were a frequent feature of temperance movement activity, with dialogues and recitations performed by young people as part of the Band of Hope meetings, to plays such as The Bottle (1847) and The Drunkard’s Children (1848), which dramatised George Cruikshank’s serial graphic illustrations (Cruikshank, famously, was the illustrator for the books of Charles Dickens), performed in commercial theatres and by amateur groups.

Here, I want to tell a story about Mr G. F. Cook from the Gospel Temperance Blue Ribbon army, alias Fred Eugene – the ‘converted clown’ – a temperance advocate who, according to the Rochdale Union Board of Guardians minutes, gave an entertainment at the temperance hall in Littleborough attended by inmates of Dearnley workhouse in December 1886.

On 4th December 1886 The Rochdale Observer reports on a ‘big event’ – 12 nights of a Gospel temperance mission in Littleborough, under the management of Mr G. F. Cook, popular temperance advocate. Temperance historian Lilian Shiman reports on the rise of gospel temperance in the 1880s, triggered by the visit to England of charismatic temperance advocate Richard Booth from the US. The Gospel Temperance Blue Ribbon Army grew nationally throughout the 1880s, exhibiting a missionary zeal and a special enthusiasm to reach the poor, and injecting a renewed energy into the temperance movement in this period. Booth’s missionary model was replicated by Mr G. F. Cook, as will become clear – here, a mission of around a week to two weeks long would arrive in a town, create a ‘happening’, with a series of events building via word of mouth, leading up to a climatic and emotional final event, or what Shiman calls a ‘crisis point’ (Shiman 1988: 115). For Shiman – noting that the rise of gospel temperance coincided with an economic recession – these events provided a ‘safety valve’ for the release of anxieties of a precarious class during a time of economic depression (ibid: 121).

Mr G. F. Cook had come to somewhat notorious national prominence a few years prior to the mission at Rochdale. There are two extraordinary features of the story that follows – firstly, Cook’s invention of a fragile public persona, which exhibited a strange and potent blend of vulnerability, authenticity and dissimulation, and secondly, the dramatic structure of his mission in particular sites – in particular, his use of a religious narrative of redemption in the overall structure as well as specific segments of his mission. Here’s the story …

On 13th January 1883, The Era (a weekly newspaper known for its theatrical content) reported the sudden disappearance and attempted suicide of converted clown, Fred Eugene, a prominent temperance advocate attached to the Blue Ribbon Army. The report says that Fred had publicly announced that he was to give a Christmas breakfast for 1000 tramps and destitute people, at his own expense, but had then disappeared. The report notes that there are ‘some extraordinary disclosures’ connected to the clown.

Before exploring these disclosures – interestingly, the figure of the ‘converted clown’ is an oft-encountered persona in the temperance movement more generally – here, performers associated with itinerant circuses and fairs – mostly seen as disreputable and morally questionable forms of entertainment – are converted by temperance missions, and utilise their performance skills to give testimony on behalf of the temperance movement, sometimes raising vast sums of money. There are a few examples of expressed suspicion as to the genuine-ness of converted clowns in newspaper reports … I’ve found at least one acerbic report that noted the apparent drunkenness of one performer when giving testimony (!) as well as others that cast doubt on the respectable character of performers …

Piecing together information about Fred Eugene from local and national newspapers, we learn that this particular converted clown had spent some years giving temperance entertainments for the Blue Ribbon movement. He was known for powerful renditions of an emotional testimonial of redemption – and reports evidence Eugene’s popularity amongst audiences of both children and adults. According to Eugene’s testimony reported in detail in one report (Leicester Chronicle, 13 Jan 1883) – the clown was abandoned as a child following the death of his parents, taken in by a circus, and introduced to drink by circus performers as a reward for his successful performance of a particularly challenging acrobatic feat when 8 years old (a double somersault over 5 horses). He became a juvenile clown at 14 years – by which time he was drinking so much that he broke his back whilst performing a double somersault – over 22 horses this time. No longer able to perform in the circus, he wandered the country as an itinerant singer, earning money from singing songs in pubs, and experienced a moment of revelation on hearing a Temperance band playing ‘Ring the bells in heaven’. He converted to the temperance cause there and then and by 1883, performed testimony of his conversion from disreputable drunk clown to respectable temperance advocate had led to the conversion of 23,000 people to abstinence.

However, this testimony was, in fact, completely made up!

A report called ‘Who was Eugenie?’, reproduced from a Blue Ribbon Banner publication and published shortly after his suicide attempt (in January 1883), recounted how Eugene the converted clown, ‘our unhappy brother’, was in fact born George Frederick Cook. He came from a comfortable background and his parents – temperate Methodists – were still alive. He had turned to drink following an unhappy marriage as a 22 year old, and disappeared from his home, eventually – some years later – appearing as a new persona, Eugene the converted clown, alienated from his family but a popular and successful temperance advocate. In the days leading up to his suicide attempt, Eugene had broken his own pledge by drinking some brandy and lemonade by accident at a London railway station, travelling then by train to an inn in Yeovil, and after a week of drinking at the inn had attempted to cut his own throat. In the report, the Blue Ribbon army pledge to stand by Cook, support him back to health, and work to reconcile him with his family.

Interestingly, this incident enhanced rather than undermined Cook’s popularity! Six months later he was back on tour, delivering ‘stirring’ and ‘thrilling’ addresses at missions held across the country, and doing so well into the 1890s.

I want to close here with an examination of a part of his mission performance called ‘The Up and Down line’, as it demonstrates his metaphorical dramatization of the ‘stations of the cross’, and may be an address that he gave in Rochdale in 1886. There is a detailed report of the mission in Morpeth in April 1885 (reported in The Morpeth Herald, 4 Apr 1885). The report describes Cook as medium build with long black hair ‘and evidently of a nervous and sympathetic nature’. The opening event of the mission starts with hymns as the audience assembles and speakers take their seats. A solo of sacred song is given – ‘I left it all with Jesus long ago’ – accompanied by a harmonium. The Chair gives a speech saying that the current commercial depression demonstrates that the country is ‘reaping what is has sown’ – that is, paying the penalty of the folly of drinking (the temperance movement tended to blame multiple social ills – poverty, economic crisis – on the waste of resources and talent on drink). He comments that the mission will include a week of addresses in different sites in the town, including visits to the homes of drinkers. There is a hymn and a collection to cover expenses. Cook gives an address, there is another hymn, the singing of the doxology, and invitation to take the pledge.

The next night Cook gives ‘his deservedly famous lecture on “The Down Line” … a most ingeniously constructed lecture, and being delivered in splendid style, both in the grave and gay passages, it fairly delighted the audience’. The ‘Down Line’ is a railway track owned by ‘The Trade’, with its Directors being the 650 MPs and JPs who grant drink licenses, and then fine people for travelling too far. The shareholders are malsters, brewers, distillers; the stationmasters are publicans; the porters are the police; and the engine driver is ‘Danger’. The stations are ‘little drop’, ‘enjoyment’, ‘I like it’, ‘I’ll have it’, ‘I care for nobody’, ‘nobody cares for me’, and finally ‘desperation’. Here, ‘the illustrations brought in to show off each station were told with rare dramatic power, and it will be a long time before the terribly realistic pictures shown to the audience at “desperation” station, are effaced from their memories’. The following night Cook gave an address called ‘The Up Line’. The directors here are ‘Faith in God’, who guides us, ‘Hope’, for those we wish to rescue, and ‘Charity’, for those in the drink business. Cook stresses that ‘the lowest sunk could at once become shareholders, and the lower they had been sunk the sooner was a “dividend” declared’. The porters are workers and advocates, the driver is ‘Safety’ and the guard is ‘God’. There are three classes on the train that travels on this line – first class is ‘Prevention is better than cure’, second class is ‘Example for weaker brethren’, and third class is ‘Necessity for poor degraded drunkards’. The stations are ‘leave it alone’, ‘happier home’, ‘pure enjoyment’, ‘I care for somebody’, and ‘somebody cares for me’.

The dramatic high point of the address occurs at a junction on the line, where the ‘Up Line’ joins with ‘the Christian railway, and between the two sets of rails there was ever flowing the fountain of Christ’s blood, “opened for sin and uncleanness”’.

What does all this mean for understanding theatre and the poor? I’m haven’t got anything conclusive to say here, but I’m interested in exploring this and other modes of temperance entertainment for the poor as a fledgling social theatre. As part of this – the idea of the ‘mission’ and ‘missionary’ in the context of social and educational theatre practice might also perhaps highlight the importance of social modes of religiosity to the histories of applied and social theatre. I’m also interested in Brian Harrison’s argument – in his extensive study of the Victorians and alcoholic consumption – that the temperance movement promoted an idea that an inclusive and equitable social order was possible by determinedly including the poor drunkard in the social imaginary: ‘haltingly, sometimes inconsistently, but ultimately decisively, they were widening the bounds of tolerance and understanding’ (Harrison 1994). As such, temperance entertainments offer a form of emotional training and a disciplining of the affective realm that may be worth thinking more about, and that perhaps resonates with current discussions around the politics of affect in applied theatre. I am also interested in the themes of gift, sacrifice and dirt that feature in the religious trajectory of this narrative – and their resonances with the notion of the ‘gift’ of theatre (the ambiguities of which Helen Nicholson has explored in her book Applied drama in 2005).

I’m not sure where this thought might go – but is there also something interesting about Fred Eugene alias George Frederick Cook himself? – his itinerancy, fragility (in his clown and rescued persona) and charisma – that perhaps might map onto the activist and precarious modes of performed labour in applied theatre practices … this may be pushing things a little too far, perhaps, but are there ways in which the investment of self, and modes of self exploitation (arguably) in much activist and social theatre are prefigured in the story of this converted clown?

References

Harrison, Brian. 1994. Drink and the Victorians. Second edn. Keele University Press

Nicholson, Helen. 2005. Applied drama: the gift of theatre. Hampshire & New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Shiman, Lilian. 1988. Crusade against drink in Victorian England. London: The Macmillan Press

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.