Audible and voluble expressions – part 2 (1887)

Post by Jenny Hughes

I’ve been researching theatrical entertainments in Victorian workhouses, and have come across an extraordinary range of work that might be described as ‘fledgling’ social theatre from the 19th century, from missionary and temperance theatricals to solidarity and charity performances by popular performers, to amateur performances by local glee clubs, choirs, working men’s bands, amongst others. For more information see – ‘The only way is Rochdale’ – 1, 2 and 3 on this blog.

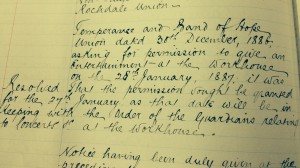

When looking at the minutes of Dearnley workhouse in Rochdale following its opening in 1877, I came across this note, from 6 January 1887 – ‘Temperance and Band of Hope Union dated 30th December 1886 asking for permission to give an entertainment at the workhouse on the 28th January, 1887’ – prompting some research into the Band of Hope movement.

The first national organisation to provide social and recreational activity for children, the Band of Hope was formally constituted in Leeds in 1847. Over subsequent decades, it engaged vast numbers of young people across Britain and its colonies, still existing today as Hope UK – offering drug and alcohol education to young people. A prototype applied theatre network for children and young people, it generated an extensive archive of recitations, dialogues and short plays for performance by children which, taken together, provide an extraordinary insight into the uses of theatre for personal, health and citizenship education in the 19th century.

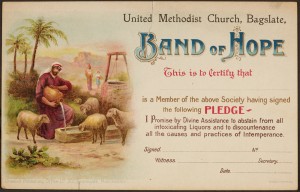

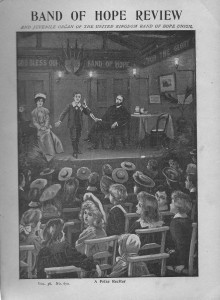

Robert Tyler, in a history of the Band of Hope published in 1946, argues that the movement was innovative in its commitment to develop young people as powerful presences in their communities. As he says, in a period when children were expected to ‘be seen and not heard … the Band of Hope was allowing its young members to express themselves audibly and often volubly’ (1946: 39). Typically, Band of Hope members attended a weekly evening meeting which contained an opening address, sometimes given by a young person, followed by a hymn, and perhaps an input by a visiting speaker. At the beginning or the end of the meeting the pledge to abstinence would be repeated – and new members signed a pledge card and received a ribbon to wear. As Annemarie McAllister comments ‘the performance elements of the evening’ were ‘the main attraction’ (2011: 11).

The recitations and dialogues performed would focus on abstinence, but also advocated a range of moral and civic virtues – labour, effort, perseverance, hope, a peaceful home, trusting in the providence of god, appreciating the beautiful outdoors, drinking water, reading, doing one’s duty – as well as warnings against vices – drinking, smoking, snuff, playing cards, going to the theatre. They utilised a variety of forms – there are trials, melodramas, councils of war, wars (against the Demon Drink), sermons, miraculous conversions, debates, arguments, appeals, and I’ve even found a play ending in a water fight! In terms of tone of speech, many adopt a ‘dialogue’ register, in that the style of exposition that seems demanded exhibits aspects of the classic Renaissance dialogue form – moral assertion, call and response, statement, appeal, rhetorical phrasing and discussion.

Overall, the plays appeal to young people and adults in a community to become temperate – to stop drinking and as a result, create a more harmonious and equitable world. Directed at and driven by working people, the temperance movement, in Brian Harrison’s terms, ‘lost all sense of proportion’ in assigning all manner of social ills to drinking – including poverty, economic crisis, disease, crime et cetera. Temperance also provided social relief and extended the boundaries of compassion and tolerance through not giving up on the poor, the drunkard and the wayward – and as such – for Harrison – temperance activity worked against laissez faire economic ideology dominant in this period. This tension – between the mimesis of work discipline – and an impetus to open up to the abandoned – is central to my own reading of Band of Hope performance practices.

There was social cache to be earned from learning and performing dialogues and recitations by heart, and many seem – in terms of modern standards – very long, and must have demanded extensive preparation and rehearsal time. Here’s an excerpt from an example (published in the Band of Hope Entertainer in 1893) – a favourite of mine – but note, this is only 30 lines from a 100 + line piece.

‘Teetotal Transformation scenes’

Original. To be recited by a girl, dressed in as fairylike a manner as possible. White muslin dress with tinsel ornaments, spangles, &c., a crown or chaplet of flowers on her head, and a wand in her hand, which she waves slowly during her recitation of lines as marked *.

My name is Mab, the Fairy Queen,

And, wandering o’er the world, I’ve seen

Full many a strange and startling sight,

Causing me wonder and affright.

Both social peace, and social storm,

And human crimes in every form;

And yet the saddest sight, I think,

Lies in the havoc wrought by drink!

Ah! Where drink enters love departs –

Leaving wrecked homes and broken hearts! …

I’ve come tonight that I might show

How I would change these scenes of woe.

I’d wave my wand, and they should be

Teetotally transformed by me! *

… You may not live in fairyland,

Your station may be far from grand;

No fairy wand have you to wave, *

And yet you may drink’s victims save.

If to the Temperance work you give

Your hands and hearts, and strive to live

Up to your pledge, your influence

Will powerful be in every sense –

Example, as you each must know,

Will further than all precept go;

However low your lot may be,

It may turn out yet happily.

Two causes fight for manfully –

Religion and Sobriety!

Then everywhere will be, I ween, *

A Teetotal Transformation Scene!’ *

Like many Band of Hope recitations and dialogues – this recitation positions the young person as a socially and politically conscious community leader, and through humorous performance, celebrates their ‘audible and voluble’ presence (to repeat Tyler’s words). As historian Stephanie Olsen comments, youth organisations in this period incorporated a blend of Romantic and utilitarian discourse: ‘a distinctly unromantic corruption of Wordsworth’s “child as father of the man”’ (2014: 95). Here, there was a belief that ‘the child exemplar, pure of heart and noble of spirit, could shape not only his child peers, but also the adults in his life’ (2014: 4). For Olsen, the child exemplar was a beacon for the ‘human race’, a construction accruing shifting nationalistic, Christian, communitarian and liberal emphases.

To add a perspective from theatre studies, Anne Varty – in her study Children and Theatre in Victorian Britain (2008, Palgrave) – notes how Romantic discourses led to the child becoming symbolised as a form of ‘savage innocence’. Here, the child on stage is a figure of public fascination, providing a spectacle of ‘controlled’ and ‘scrutinised’ savagery which culminates in the child’s assimilation into civilisation, as well as an affirmation of the superiority of Victorian society (2008: 15).

Band of Hope theatricals often reflect all this – offering gendered disciplinary dramas of self-repression, and here the voices and bodies of children do not seem to belong to themselves. Instead, they are scripted in ways that integrate the child as a legible form inside the imaginary of a strong community, one that is linked to the maintenance of the social body variously called nation, industry, family and empire.

However, it is important to not too quickly dismiss these performances as disciplinary in a negative sense. The performance of self as respectable represents a practical defence against threats of poverty and unemployment, and participation in improving cultural activity – including membership of the Band of Hope – helped to hold the social world open. As part of this – working alongside other young people, with supportive adults, accessing opportunities for friendship, intellectual stimulation and light-heartedness after the monotony of the working day, adds up to an inhabitation of time and space that exhibits but is not reducible to its broader disciplinary scriptings. The very clear and certain messages contained in the texts, might also have helped to create a strong and reliable sense of reality, truth, and goodness – holding a young person steady as they make their way through a precarious world.

A final note – one of plethora of penny pamphlets containing recitations and dialogues for Band of Hope groups was called The Onward Reciter, published from 1871 to 1917 – a publication that had a national circulation and was published by the Lancashire and Cheshire Band of Hope Union. This, the largest union outside of London, later had its own building on Deansgate in Manchester – which is still there:

You can find an interesting history of the building here, with some great visuals of its insides as well as a commentated You Tube clip of a Band of Hope procession in 1901

Sources of information on the Band of Hope

Annemarie McAllister. 2011. ‘“The Lives and souls of the children”: the Band of Hope in the North West’ Manchester Region Historical Review 22: 1-18 (you can follow Annmarie’s work at Demon Drink Extra – https://demondrinkextra.wordpress.com/ and @demon_drink)

Stephanie Olsen. 2014. Juvenile Nation: Youth, Emotions and the Making of the Modern British Citizen 1880-1914. London: Bloomsbury

Lilian Shiman. 1988. Crusade against drink in Victorian England. London: The Macmillan Press

Lilian Shiman. 1973 ‘The Band of Hope Movement: Respectable recreation for working-class children’ Victorian Studies 17, 1: 49-74

Robert Tyler. 1946. The Hope of the Race. United Kingdom Band of Hope Union: Hope Press

And, for a great introduction to temperance, go to Brian Harrison. 1994. (Second edn.) Drink and the Victorians Keele University Press

I am grateful to the Theatre and Performance Research Association conference Applied and Social Theatre working group for allowing me to present some of this research at Worcester University in September (2015). The research is also be part of a chapter ‘A pre-history of applied theatre: work, house, perform’ in Jenny Hughes & Helen Nicholson (eds) Critical Perspectives in Applied Theatre, Cambridge University Press (forthcoming)

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.